Does Public Space Really Belong to the Public?

A collaboration with Chicago Public Art Group brings to life a Council report exploring the racist origins of Chicagoland's public beach policies.

What happens when you translate policy into art? While these two realms are seemingly unrelated, art offers a unique opportunity to facilitate public conversations about complex policies that would otherwise be inaccessible. Art can bring policy reports to life by transferring research from “pdf to people” and allocating creative agency to artists. Though art may not be able to encapsulate every piece of information within a policy report, it has the ability to resonate with communities in unparalleled ways.

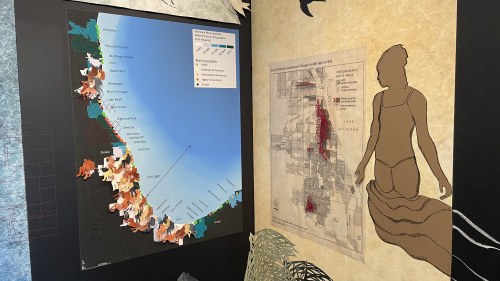

In a collaboration with the Chicago Public Art Group, a Council research report, “The Right to the Shoreline: Race, Exclusion, and Public Beaches in Metropolitan Chicago,'' came to life through an interpretive art installation at the Evanston Art Center from July 7-27. Written by Sam Kling, director of global cities research at the Council, and Lucas Stephens, now a policy associate at the Nicholas Institute at Duke University, the report explores the impact of the racist origins of Chicagoland’s public beach policies that continues to have racially discriminatory effects today.

The report outlines both direct and indirect mechanisms that municipalities have used to enforce segregation along Lake Michigan beaches stretching from Indiana to Wisconsin, including restrictive covenants, redlining, steering, zoning, and fees. Kling and Stephens also emphasize the detrimental role residency requirements play in extending historical inequities of real estate into access to public space.

Lake Forest, Highland Park, Glencoe, Winnetka, and Kenilworth are among the towns with the most exclusionary beach policies. These wealthy North Shore municipalities also have the highest percentage of white residents as well as the most expensive single-day costs for non-residents to visit their beaches. Given these findings, the researchers conclude that wealthier and whiter areas, especially those neighboring more economically diverse areas, utilize the highest exclusionary policies.

Conversely, beaches in municipalities with greater diversity and a higher proportion of lower-income residents tend to be far more accessible. After clear indications from the research, Kling asserts that “access to shoreline reflects and amplifies regional geography of racial and class exclusion.” Ultimately, the central question emerges: “Who has a right to public beaches?”

In an effort to further engage the public on the important findings of the policy report, the Council collaborated with artists from the Chicago Public Art Group (CPAG) to create a set of art installations. Founded in 1970, CPAG aims to reflect the voices of diverse communities in Chicago through murals, earthworks, monuments, and other art forms that are integrated throughout the city.

CPAG’s mission to enhance public spaces and foster community participation directly aligns with the recommendations of the policy report. The artists, Sonja Henderson and Cynthia Weiss, accepted the opportunity to make the report more tangible by creating an art piece that represented its most important messages.

During a speech at the art exhibit’s opening night, Weiss explained that “it was a really interesting and compelling challenge to turn the report into art [because] they wanted the visuals to speak for themselves while also incorporating 100 words from the paper that would be striking to the audience.” Henderson expanded on this idea, noting that in making the piece, the artists strove to create a visceral experience for audiences.

The artists facilitated this by integrating pictures of Black members of Chicago communities, several elements of symbolization, and an easily comprehensible map at the crux of the report. Additionally, the artists organized an interactive element into the piece by allowing visitors to create “policy poems” by cutting and pasting words from copies of the report onto their own sheets of paper. Henderson explained that the intention of this aspect of the project was to encourage audiences to engage with the report by pulling out words and creating personal meaning.

The installation not only allows visitors to better understand the report’s findings but also instills a sense of unity and hope on the topic. The artists advocate for audiences to take action with their local government in order to ensure that the discriminatory effects of past racist policies are amended, and public space remains public for communities to experience the natural beauty of the lakeshore equally.